Further Information on Grand Theft Auto: Saskatchewan Series, 2009

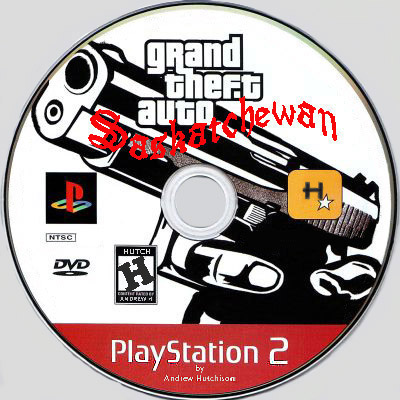

Unauthorized Playstation Video Game + Video Installation & Cover Art as Chromiographic Print Limited Editions.

I'm not going to hide it, I'm a bit of a video game nerd. What can I say, I admit it, always have been. Young at heart I guess. The games are addictive, and stress relieving all in one. They improved over the years, becoming hyper-realistic and in their relatively short history have caused some commotion. Are they too violent, are they harmful to society in some way, are they good for us? Are they art or something else. I don't really know, but I know what I like.

In the first decade of the 2000s there was a specific game, that people were up in arms about. Those playing it, and there were millions, had their arms up celebrating how good they thought it was and the media in a lot of cases had theirs up in disbelief of how violent it was. The game was Grand Theft Auto. Players could run around some imagined Californian like city, doing anything your heart desired. Steal a car, shoot a police officer or innocent bystander, rob a bank, hire a lady of the night, chase down drug runners and so on and so forth. It was always a far off city, filled with excitement and corruption.

You could be the a hero or the villain. Which ever you choose.

It was maybe too much for the time. And it wasn't for everyone, but certainly was for many.

Well, corrupting a city could be fun, I am embarrassed to admit. But you haven't lived until you've done it in Saskatchewan, where normally it's a quiet little place, it's your job now to bring the noise and crimes lacking in such a pristine locale.

Be the first play, to run guns, street race, and steal police cars in the freshly designed game.....

Grand Theft Auto: Saskatchewan

available now!

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Screen Shots from Grand Theft Auto: Saskatchewan VIDEO GAME

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Coming soon....

A more quiet atmosphere, even slower cars and way less to do, but oh you should see the wide open views.

Grand Theft Auto:

Newfoundland

Steal a Mountie's Car and enjoy the harrowing experience of being on the run, once again,

this time on our picturesque 'Rock'. Newfoundland and Labrador

All images unless otherwise stated Copyright © Andrew R. Hutchison 2000 - 2014

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

THE ART OF VIDEO GAMES

Are video games art? That question has sparked heated debates among those within the art world gaming sphere for the better part of the last two decades.

The Museum of Modern Art in New York has weighed in by establishing a collection dedicated to showcasing the best in video game design and aesthetics.

"Are video games art? They sure are, but they are also design, and a design approach is what we chose for this new foray into this universe," reads the MOMA literature on their recent show. They emphasize not only the visual quality and aesthetic experience of each game, but also the many other aspects--from the elegance of the code to the design of the player's behaviour--that pertain to the interaction based design.

A work of art is one person's reaction to life. Any definition of art that robs it of this inner response by a human creator is a worthless definition.

Visitors to the Museum of Modern Art can see Pac-Man displayed alongside Warhol’s Gold Marilyn Monroe and Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, as New York’s premier modern art gallery has officially decided video games can be called art. Video games have become an important cultural, artistic form of expression in society. They could become one of the most important forms of artistic expression in the next century. The people who apply themselves to the craft of making video games, view themselves as artists, because they absolutely are. It is an amalgam of many traditional forms of art.

The argument that video games could be art was boosted in the US last year when the Supreme Court ruled they were like other works of art and their right to free speech should be protected under the First Amendment.

The MOMA show is just the latest in a series of validations from the high art community acknowledging that video games stand next to the best in art and are taking their place. The shift has been gradual over the past 15 years, but those taking positions of influence now are those who grew up with video games.

The most cursory look at video games raises several interesting issues that have yet to receive any consideration in the philosophy of art, such as: If video-games are art, what kind of art are they? Are they more closely related to film, or are they similar to performance arts? Perhaps they are more akin to competitive sports and games like diving and chess? Can we even define “video game” or “game”? We often say that video games are interactive, but what is interactivity and what are the effects of interactivity on eliciting emotional responses from players?

In some sectors of academia video games have recently become a subject of attention: a few MFA Programs exist to train artists in the technology used in game development and Ph.D. programs devoted to the study of video games and interactive media, such as the program at Georgia Tech, are starting to pop up. Within the past few years, a handful of books have been published on video game theory. Although some philosophers have begun writing on issues dealing with video games, philosophers of art have completely ignored the subject.

The primary question for philosophical aesthetics is whether some video games should be considered as art. When looking at recent examples, it is apparent that video games have moved far beyond the primitive state of “Pong.” Today, games such as “Grand Theft Auto” and “Assassins' Creed” structure themselves around elaborate narratives that may take upwards of twenty+ hours to complete. Even if one lacks first-hand experience playing a game, a superficial glance reveals the narrative complexity that would prompt several movies to be made based on video games. Though one may say that many video games lack artistic value, the same can be said for some products of any art-form without calling the value of the whole enterprise into question. Perhaps it is best if we approach the medium’s current state as similar to that of film in the late 19th century: we can see a continuum from the relatively primitive Lumière actualities such as “Arrival of the Train” to the fully-realized promise of the art-form that is obvious only decades later in the works of Fritz Lang.

Unfortunately, there has been no sustained argument on either side of the video games as art debate. An early attempt to defend the notion of games as art can be found in Chris Crawford’s book 'The Art of Computer Game Design'. Although academics have not sustained the debate, the issue has remained active in court cases involving video games and the First Amendment. For instance, in American Amusement vs Kendrick, Richard Posner argues that video games should be given full First Amendment protection partly because they share themes with the history of literature and they often try to evoke similar emotional responses from their audiences. Although there have also been several journalistic attempts to declare video games outside the realm of art – and a comparable number of court cases in agreement – no one has carefully sorted out the issue. Making matters worse, the caliber of the debate is fairly low: most arguments against the video- games-as-art position merely repeat some form of the primitive entertainment-art distinction.

The most salient feature of the debate is the absence of the most common criticism of mass art – the passivity charge. Given the interactive nature of video games, there is simply no room for the charge of passivity. Video game players are anything but mentally or intellectually passive during typical game play. Video games are possibly the first co-creative, mechanically reproduced form of art: they are mass artworks shaped by audience input. Interactivity marks a crucial distinction between decidedly non-interactive mass art forms such as film, novels, and recorded music and new interactive mass art forms. Sadly, this important distinction has yet to be examined in any satisfactory manner with very little written or discussed on the subject of the relationship between Art and Play.

I'm of the first generation to grow up with computers and video games, we are about to come up on 40. We’re still playing video games. But we are also having children. We are approaching some semblance of middle-aged respectability (however reluctantly). The traditional institutions of business, government and culture are gradually becoming our own. One of us will eventually become the first President of the United States or Prime Minister of Canada to grow up playing video games, the way Bill Clinton represented the first generation to grow up listening to rock ’n’ roll. But we’re not quite there yet. In the meantime we can celebrate our favourite hobby’s successful assimilation into the mainstream of North American life.

Last year the Supreme Court conferred video games full First Amendment recognition as a protected form of human expression. Now the Smithsonian, the U.S. nation’s official education and research institute, has decreed our little bleeps and bloops worthy of its hallowed granite and marble, quite literally down the hall from paintings and sculptures that define the country’s cultural heritage.

“The Art of Video Games” exhibition does not represent the brash young cultural newcomer kicking in the doors of officialdom, belching loudly and declaring that he is taking over. Rather, it represents a humble penitent carefully putting on his least- threatening outfit and being allowed to take a place in the corner.

But hey, at least we’re through the door now. Once the grown-ups get used to having us in here, we can start to get frisky. There will be a time when museums spend brainpower putting together deeply intelligent exhibitions on representations of violence in video games or on depictions of women in the games of various cultures. Exhibitions will explore the emotional impact of modes of storytelling in games. In other words, museums will one day bring the same intellectual attention to the substantive meaning of video game exhibitions as they do for, say, painting exhibitions.

They're not ready for it yet, though.

The Smithsonian exhibition presents four games for the PlayStation 2, the best-selling home game console in history, without mentioning the game that defined that machine, the profane and violent Grand Theft Auto III. In fact none of the Grand Theft Auto games (or the other masterpiece from Rockstar Games, Red Dead Redemption) were included. For an exhibition that wants to demonstrate the deep storytelling and characterization in games, their absence is unfathomable.

Likewise, it is easy to understand why the Smithsonian American Art Museum does not point out that half of the 80 featured games in the show were primarily made in Japan. There are actually more Japanese games than American games in the main part of the exhibition. (A few are Canadian and European productions.) This question of why American consumers have flocked to Japanese games when they turn up their noses to almost all cultural imports beyond British rock bands is not one that the museum appears eager to raise.

Yet these are all the cavils of someone who has spent decades playing video games. I recognize why this exhibition must be as it is: Video games are just now, finally, earning the validation of our parents’ generation. We have now seen our treasured game systems go from under the Christmas trees of our youth to under glass at the Museum.

And it feels pretty darn good.